Hans van de Waarsenburg's Bergen

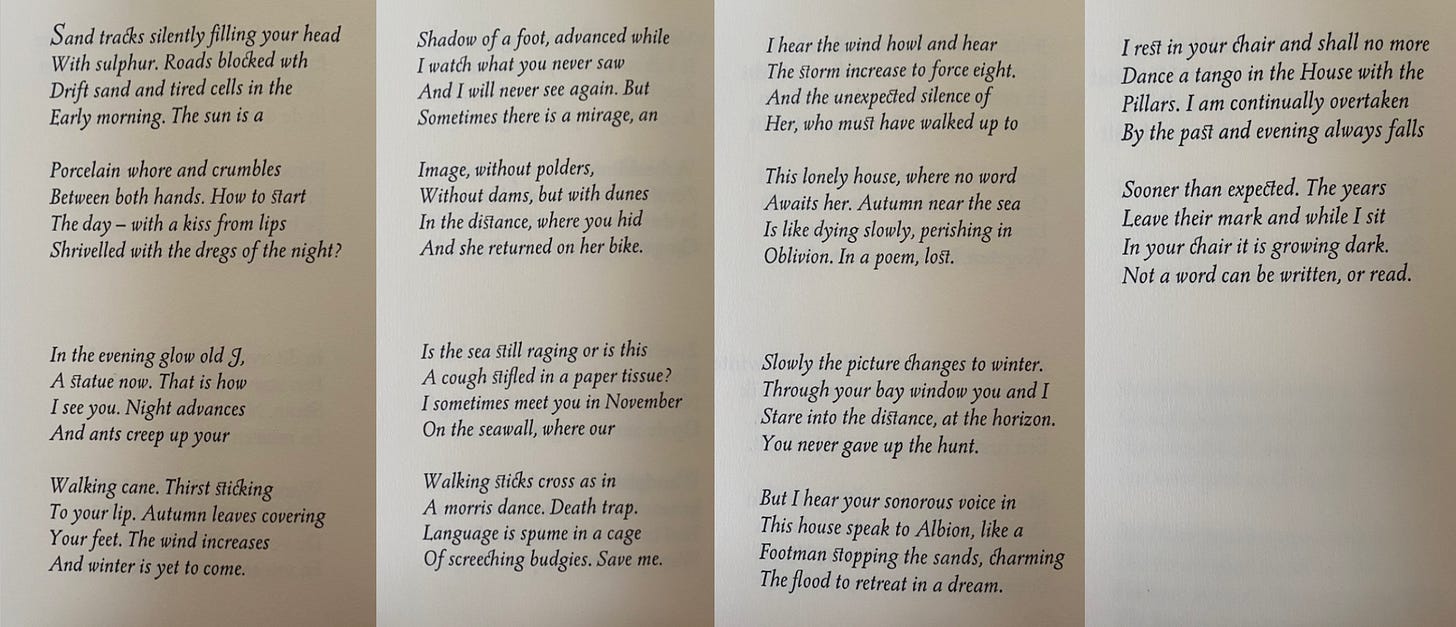

I have read one poem by Hans van de Waarsenburg, one poem published as a slim cycle titled Bergen. Printed by Hans van Eijk through his press In de Bonnefant, Bergen comes containing the original Dutch and an English translation by Peter Boreas. There seem to be several In de Bonnefant editions of Waarsenburg poems floating around, and one selected volume from Eyewear Publishing — all translated by Boreas. Bergen, however, appears rather unavailable, and so in an effort to make my brief notes on it clearer, and more, with the thought that others might appreciate the work as I have, I’ve included Boreas’s translation below —

What first held my attention was the fourth stanza’s, “The wind increases / And winter is yet to come.” These lines brought to mind echoes of Aleksander Blok’s “A Voice from the Chorus,”

“So, quieter than water now,

lower than grass, be contented

with your lives. Children, if you knew

the darkness of the days ahead!”

and Ingeborg Bachmann’s “Borrowed Time”

“Don’t look around.

Lace up your boots.

Chase back the hounds.

Throw the fish into the sea.

Put out the lupines!

Harder days are coming.”

The differences—Blok dourly conditioning contented hands, Bachman insisting on preparedness—Waarsenburg sets his pronouncement with no prescription, it is less oracular, more mundane, at face value it is mere observation; yes, comes the wind, yes, then winter.

Here, perception moves beyond the mere, beyond the minutiae of the image, the poem is never satisfied with its own observation—the speaker feels an age that might serve a wisdom found in some beauty of the natural world—we can sense a slow rocking in the final stanza’s chair from the very first line—but there is no satisfaction in any experience; the drift sand and tired cells of the early morning must meet “lips shriveled with the dregs of night.” The raging sea, such a world unto the whole fringe of vision, is noticed as nothing but a “cough stifled in a paper tissue.” And perhaps most telling, that same water as the weather changes, “Autumn near the sea / Is like dying slowly.” Most telling because it makes clear the strife of representation, the image gives no heroic gesture; the sight as symbol has crumbled, the image is only as substantive as the time which shifted its being seen, all that comes is to be “overtaken / by the past.” The point, then, that this is not morose, that in this envisioning there is much given beyond an awe of morning. In The Entryway Into the Garden Pierre-Albert Jourdan writes:

In this lush garden, you sometimes nearly suffocate. It is perhaps a cliché, but you cannot approach beauty. Between it and us there is such a gap that it cannot help but provoke shame when we face this world that we have built without ever consulting innate grace—destroying the grace instead with something strongly resembling satisfaction.

Waarsenburg sees no deliverance in this grace, the poem finds its life in Jourdan’s gap, it approaches the natural world without an end, and instead takes what there is as experience which has already ended. This is not final, but somewhere closer to a beginning, it is constitutive of value; similar to Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s note in his Book of Friends:

“Man perceives in the world only what already lies within him; but to perceive what lies within him man needs the world; for this, however, activity and suffering are indispensable.”

Waarsenburg perceives what is within him through the world: “In the evening glow, old J, / A statue now. That is how / I see you.”—He sees only through the evening glow, but it is his seeing, his consultation of grace. This grace stands apart from satisfaction in its being both active and suffering, what’s satisfied is static and ended, what’s indispensable in Waarsenburg’s approach is time; the atomic frenzy of every instant shooting through, the affliction felt in activity’s passing; “Sooner than expected. The years / Leave their mark and while I sit / In your chair it is growing dark.”

The type of line that builds Bergen moves towards something vestigial. In The Vestige of Art Jean-Luc Nancy writes that the essence of art is that which “remains withdrawn from the image,” Nancy differentiates this vestigial notion from something more preoccupied with representation, “It is not a ruin, which is the eroded remains of a presence; it is just a touch right at the ground.” See the movement of Nancy’s sentence in Pound’s River-Merchant’s Wife,

“The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind.

The paired butterflies are already yellow with August

Over the grass in the West garden;

They hurt me. I grow older.”

Here, the eroded remains of early autumn break into the final touch—They hurt me. I grow older.—this disclosure withdraws from the earlier image and shoots a trace, as if a nerve was struck, through the poem in both directions; the line is glimpsed between ruins as a step settled in still wet mud, it is suddenly known that a second is present. Another stands before the grass in the West garden, the speaker is no longer purely susurrating stone, incanting an image for hands which hold the book; but is whispering to themselves, curling waves from the reader’s eye back to their own ear, and whomever happens to have said book in hand takes note; it seems a room stumbled into, a lone figure on the floor, their chest tightening, their hands clutching where the air won’t travel—the poem is present in its statuary and then suddenly gone to the strain of something soft on private breath, to how that whisper brings us to our own lives. This is the line Waarsenburg favors in Bergen, not one that speaks to the reader, but one that, as Blanchot writes, forces the reader to imagine the hand that is writing—in that imagination the reader is spoken through and created—the reader takes part in the generative movement of the hand at work, it is a line which says, in every moment, as Borges quotes Silesius, “Friend, this is enough. Should you wish to read more, / Go and yourself become the writing, yourself the essence.”

The difficulty then, is that despite the line proclaiming its words are enough, despite the line sending the reader out towards the world, we are always figured to return, to remain within. And within we remain, as the howling winds obliterate the cause an end alone persists, and if there is living with ends alone there is nothing left but always being born; here is the moment wherein the poem moves from ruin to trace, as the memory of a passerby is vanished, and the glint on the rim of a footstep’s depression catches the slick corner of an eye, there is a world begun. Slowly the picture changes to winter; Waarsenburg from his rocker, catching autumn near the sea with a procession of his hand; without concerted detail or conspicuous lithe, from the pen comes smoke without fire, and snow has fallen only from branches which carry it already fell—as Yves Bonnefoy ends a poem on Poussin:

“An old man, at evening, astonished,

But still determined to say the colour,

Late, his hand become a mortal thing.”